One Health in Action - Emily Jajeh

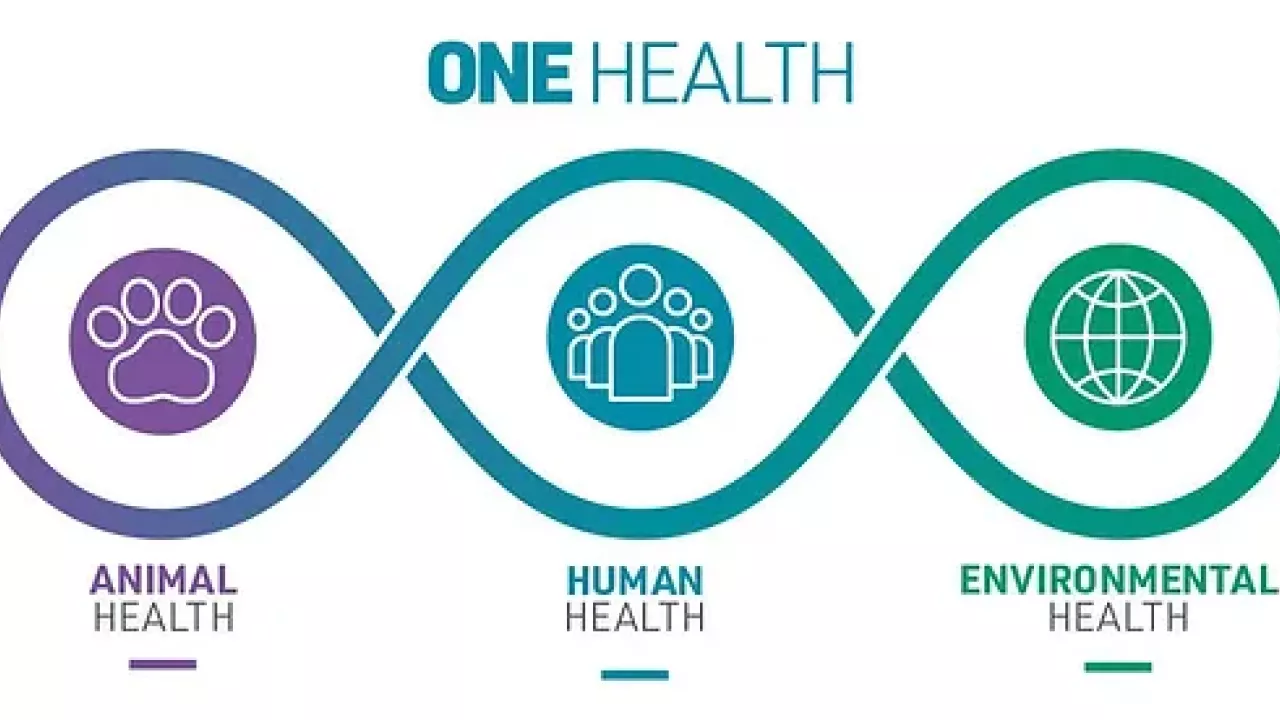

One Health is a central component of the GDB major and having a thorough

understanding of One Health can not only help you in your GDB classes, but will

also help shape your perception of disease control and prevention throughout your

career. One Health is a disease control and prevention approach that recognizes

the connection of the health of people to the health of animals and the environment

(CDC 2024). A One Health approach involves the collaboration of experts from

multiple disciplines working with local leaders, community members, and other

relevant stakeholders to achieve optimal health outcomes. This approach

recognizes the importance of involving the community or population of interest in

the discussion and implementation of disease control strategies. A good One

Health strategy will involve not only medical doctors, biologists, ecologists, and

other scientists, but also community members and leaders. It’s important to

involve the community to ensure that the solutions implemented address the issues

that they feel are the most pertinent, and that those solutions are respectful to

local customs and culture.

understanding of One Health can not only help you in your GDB classes, but will

also help shape your perception of disease control and prevention throughout your

career. One Health is a disease control and prevention approach that recognizes

the connection of the health of people to the health of animals and the environment

(CDC 2024). A One Health approach involves the collaboration of experts from

multiple disciplines working with local leaders, community members, and other

relevant stakeholders to achieve optimal health outcomes. This approach

recognizes the importance of involving the community or population of interest in

the discussion and implementation of disease control strategies. A good One

Health strategy will involve not only medical doctors, biologists, ecologists, and

other scientists, but also community members and leaders. It’s important to

involve the community to ensure that the solutions implemented address the issues

that they feel are the most pertinent, and that those solutions are respectful to

local customs and culture.

There are many examples of disease outbreaks that would benefit from the

implementation of a One Health approach. For example, in 2013-2015, there was

an Ebola outbreak in West Africa (Mwangi, Figueiredo, and Criscitiello 2016). This

outbreak hit the affected West African regions quite hard, largely due to the added

mortality from other neglected tropical diseases that overwhelmed health care

systems. Ebola can be spread from person to person, which contributed to its rapid

spread, but it also can be spread zoonotically, namely from the handling and

consumption of bushmeat. First responders to the outbreak had a clear

understanding of the human-to-human transmission of the disease, but they did not

give as much recognition to the animal-to-human transmission. In addition to the

lack of proper attention towards the zoonotic origin of the disease, the burial rites

practiced by many of the affected communities exposed more people to the virus.

Ebola virus disease (EVD) is a zoonotic disease; bats have been found to be the

main reservoir host, and contact with bats or other infected animals can spread the

virus to humans (Hussein 2023). Human-to-human transmission occurs through

direct contact with bodily fluids. EVD causes flu like symptoms, vomiting, and

diarrhea, and rapidly evolves into a hemorrhagic fever.

The burial traditions practiced in the communities affected by Ebola often involved

close contact with the infected individual’s corpse, which contributed to the spread

of the infection. However, the health workers responding to the outbreak only

considered the health risks of the burial rites and ignored the cultural significance

of the traditional burial practices (Maxmen 2015). The dismissal of local customs

resulted in resistance from affected communities. Community members retaliated

against the health workers disrespecting their burial traditions; for example, some

people would throw stones at ambulance drivers, attack health workers, and hide

their sick relatives in the forest. These retaliation events contributed to the rapid

spread of the disease, and could have been easily avoided by having an open

discourse with local communities and demonstrating respect for their traditions.

For example, in June of 2014, a pregnant Guinean woman died from Ebola. Her

fellow community members insisted that the woman’s fetus must be removed from

her body before burial so as to not disturb the world’s natural cycles. Rather than

force the village to compromise their beliefs and bury the body anyway for the sake

of decreasing the risk of further contact with the virus, they called in an

anthropologist from Cameroon. This anthropologist worked with the villagers to

find a compromise; by communicating with elders in the community, the

anthropologist was able to find a ritual that would both prevent further contact

with the infected corpse and protect the natural cycles from being disrupted.

We can learn from the Ebola outbreak in 2013 and create better strategies to

respond to disease outbreaks in the future. From my experience as a GDB student

and from my experience researching in Africa, it is clear to me that the key to

providing effective, ethical health care interventions is acting with cultural

humility, respect, and openness. The first responses to the 2013 Ebola outbreak

were dismissive and disrespectful of the culture of the communities they were

attempting to help. Their lack of attention towards the importance of earing the

community’s trust and respect made their intervention strategies less effective.

Their strategies would have been more effective and ethical if the One Health

approach was properly employed. A multidisciplinary team would help target the

disease itself and the sectors of health it’s impacting from multiple fronts. For

example, some team members experts in zoology, ecology, and/or wildlife biology

would focus on studying the transmission route from animals to humans, and work

on solutions to controlling that disease pathway. At the same time, public health

specialists, anthropologists, social workers, and community leaders would work

together to understand why people are coming into contact with the animals and

work with the community to form a plan for how they can provide health education

for how to limit interactions with wildlife or interact more safely. On the medical

side, teams of doctors, nurses, and other healthcare workers would work together

as a team with the local leaders and healers to create a plan to treat infected

individuals and limit the risk of further infection. All of these teams, however, will

only be able to promote positive change if they prioritize working with the

community rather than against them. They need to focus on gaining the trust of the

community by listening to their needs and being open to learning new ways to

approach disease control based on the beliefs and customs of the local community.

This involves the aid team being willing to listen and make compromises, and

being open to addressing the crises that the community feels are most important to

address first. Sometimes this looks like working with the community to facilitate a

ritual that will address issues the community feels are most important before

addressing the issues that the aid team feels are most urgent. Showing interest in

and respect for a communities beliefs, values, and traditions builds trust and will

facilitate more open communication between the community members and aid

teams that will result in more effective and sustainable disease control outcomes.

For example, in June of 2014, a pregnant Guinean woman died from Ebola. Her

fellow community members insisted that the woman’s fetus must be removed from

her body before burial so as to not disturb the world’s natural cycles. Rather than

force the village to compromise their beliefs and bury the body anyway for the sake

of decreasing the risk of further contact with the virus, they called in an

anthropologist from Cameroon. This anthropologist worked with the villagers to

find a compromise; by communicating with elders in the community, the

anthropologist was able to find a ritual that would both prevent further contact

with the infected corpse and protect the natural cycles from being disrupted.

We can learn from the Ebola outbreak in 2013 and create better strategies to

respond to disease outbreaks in the future. From my experience as a GDB student

and from my experience researching in Africa, it is clear to me that the key to

providing effective, ethical health care interventions is acting with cultural

humility, respect, and openness. The first responses to the 2013 Ebola outbreak

were dismissive and disrespectful of the culture of the communities they were

attempting to help. Their lack of attention towards the importance of earing the

community’s trust and respect made their intervention strategies less effective.

Their strategies would have been more effective and ethical if the One Health

approach was properly employed. A multidisciplinary team would help target the

disease itself and the sectors of health it’s impacting from multiple fronts. For

example, some team members experts in zoology, ecology, and/or wildlife biology

would focus on studying the transmission route from animals to humans, and work

on solutions to controlling that disease pathway. At the same time, public health

specialists, anthropologists, social workers, and community leaders would work

together to understand why people are coming into contact with the animals and

work with the community to form a plan for how they can provide health education

for how to limit interactions with wildlife or interact more safely. On the medical

side, teams of doctors, nurses, and other healthcare workers would work together

as a team with the local leaders and healers to create a plan to treat infected

individuals and limit the risk of further infection. All of these teams, however, will

only be able to promote positive change if they prioritize working with the

community rather than against them. They need to focus on gaining the trust of the

community by listening to their needs and being open to learning new ways to

approach disease control based on the beliefs and customs of the local community.

This involves the aid team being willing to listen and make compromises, and

being open to addressing the crises that the community feels are most important to

address first. Sometimes this looks like working with the community to facilitate a

ritual that will address issues the community feels are most important before

addressing the issues that the aid team feels are most urgent. Showing interest in

and respect for a communities beliefs, values, and traditions builds trust and will

facilitate more open communication between the community members and aid

teams that will result in more effective and sustainable disease control outcomes.

References

CDC. 2024. “About One Health.” One Health. November 21, 2024.

https://www.cdc.gov/one-

health/about/index.html.

Hussein, Hassan Abdi. 2023. “Brief Review on Ebola Virus Disease and One Health

Approach.” Heliyon 9

(8). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2023.e19036.

Maxmen, Amy. 2015. “How the Fight Against Ebola Tested a Culture’s Traditions.”

National Geographic.

January 30, 2015.

https://www.nationalgeographic.com/adventure/article/150130-ebola-virus-

outbreak-epidemic-sierra-leone-funerals-1.

Mwangi, Waithaka, Paul de Figueiredo, and Michael F. Criscitiello. 2016. “One

Health: Addressing

Global Challenges at the Nexus of Human, Animal, and Environmental

Health.” PLOS Pathogens 12

(9): e1005731. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.ppat.1005731.

CDC. 2024. “About One Health.” One Health. November 21, 2024.

https://www.cdc.gov/one-

health/about/index.html.

Hussein, Hassan Abdi. 2023. “Brief Review on Ebola Virus Disease and One Health

Approach.” Heliyon 9

(8). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2023.e19036.

Maxmen, Amy. 2015. “How the Fight Against Ebola Tested a Culture’s Traditions.”

National Geographic.

January 30, 2015.

https://www.nationalgeographic.com/adventure/article/150130-ebola-virus-

outbreak-epidemic-sierra-leone-funerals-1.

Mwangi, Waithaka, Paul de Figueiredo, and Michael F. Criscitiello. 2016. “One

Health: Addressing

Global Challenges at the Nexus of Human, Animal, and Environmental

Health.” PLOS Pathogens 12

(9): e1005731. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.ppat.1005731.